by CJ Quines • on

Video game May

until then, monster train 2, aotenjo, ftl

Huh, I guess it’s been three years since my last video game blog post. Allow me to skip over my last twenty-nine months and fifty-six video games, then.

Until Then

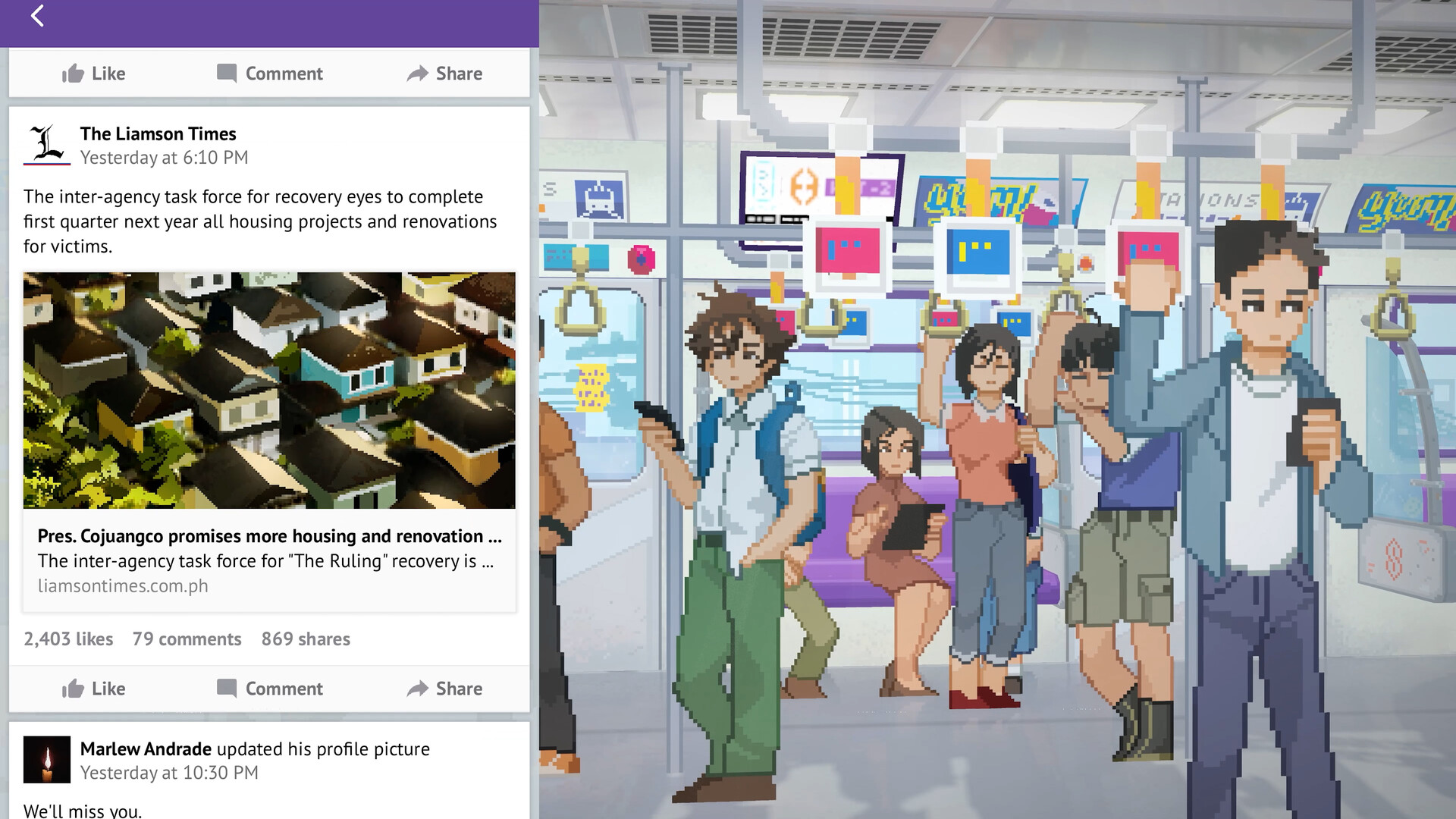

Until Then is a speculative coming-of-age visual novel set in a metropolitan area that’s legally distinct from Metro Manila. A friend raved about how good the game was, and when I saw that the game was made by Filipinos and that it’s set in the Philippines, I knew I had to play it. I’m glad I did.

The bones of the story could have happened anywhere; it’s a bit similar to the 2016 film Your Name. But the meat of the story is flavored by its rich environmental details. Mark, our protagonist, rides a train station inspired by Katipunan station on the LRT-2, with a matching station layout and fare machines. He goes to a school that’s unmistakably a Philippine public high school, down to the color scheme and jalousie windows. That’s part of why I love this game: the LRT-2 station I’ve been to most often is Katipunan, and my high school’s old building looked exactly like Mark’s.

“But CJ,” you might say, “I’m not Filipino, will I still enjoy this game?” Yes. For one, the setting’s refreshingly different from pretty much every other VN that I’ve played, which are either fantastical, American, or Japanese, or so bland as to not have mattered. Its writing is sharp and witty, and its plot is beautiful and haunting. The cutscenes feel like film scenes, given all the attention paid to framing, blocking, and color grading.

If there’s one thing I’ll complain about, it’s how the gameplay sometimes drags. The texting scenes take too long, and some of the minigames feel overdone. But Until Then is good enough that I’ve forgiven its annoyances. I’d recommend it to anyone who loves a coming-of-age story.

Monster Train 2

Monster Train 2 is the sequel to the deckbuilding roguelike Monster Train, which is kinda like a tower defense version of Slay the Spire, a game I’ve written about before. Of my Steam games, the game I have the third-most playtime in is Monster Train, with 114 hours. I got every achievement and then I kept playing on-and-off for another year. The sequel also has the potential for me to sink a lot of hours in, oops.

The thing I like the most about Monster Train, compared to something like Slay the Spire, is that in Slay the Spire you’re expected to assemble a balanced, reasonable deck, and most wins at the highest difficulty feel like you’re scraping by, squeezing every resource. In Monster Train, to win the highest difficulty, you need to break the game. You need to assemble a combo so broken that you can outscale the enemies thrown at you. Don’t get me wrong: it’s still a hard game, and there’s no formula to winning consistently. But it feels fun in a different way than Slay the Spire does, you know?

Monster Train 2 is a lot like Monster Train. There are a handful of fundamental differences. An explicit deployment phase and an undo button make gameplay less frustrating. The new card types, equipment and rooms, feel like natural additions to gameplay. The story’s elaborated on and tied to progression. But by and large, Monster Train 2 feels like Monster Train, with a different set of clans and units and spells. Which is honestly great—the first game had a winning formula, and the devs made the correct decision to keep that.

It’s not quite as finely-tuned as the first game, though that’s understandable given how early it is; it’s still fun and generally balanced. If you haven’t played the original, I’d recommend playing that first. If you have, and you liked it, then you’d love Monster Train 2 as well. After playing more Monster Train 2, my default recommendation is to skip the first game and play Monster Train 2 first. The polish matters more than game balance, I think.

Aotenjo: Infinite Hands

Deckbuilding roguelikes are my favorite genre of video game, and Aotenjo: Infinite Hands is a deckbuilding roguelike, so I love it. Of the games in this post, Aotenjo has the shortest pitch: mahjong Balatro. The similarities are clear: you play tiles to form patterns, which score two kinds of points (fu and fan), which are multiplied and added to your score, which needs to hit a certain threshold. You can upgrade your tiles and patterns, and you can also gain artifacts, analogous to Balatro’s jokers. There are bosses with gimmicks, an ascension system, a variety of tile sets.

You’d expect that the sheer number of similarities would make it feel like a cheap Balatro clone. But it doesn’t. For one, Balatro has like a dozen poker hands, but Aotenjo has more than a hundred patterns. Unlike Balatro, the consumable items in Aotenjo have greater flexibility and come in greater supply. Both of these contribute to making Aotenjo feel more like solving a puzzle. While the locus of power in a Balatro game is almost always the jokers, in Aotenjo, there’s a greater focus on forming patterns.

If the gameplay wasn’t enough to distinguish Aotenjo as a unique offering, then the vibes certainly are. There’s an explicit story: you’re fighting demons to save a sparrow. The colors are soft and smooth, the sounds are subtle and sophisticated, and the music is soothing and serene.

The game is still in early access, and it shows. There’s lots of rough edges in the UX, and a decent chunk of the wording could be better. The opening hand can be particularly punishing in higher difficulties. It’s also more complex than Balatro is, but I consider this a feature. It’s worth giving a shot even if you’re unfamiliar with mahjong—Aotenjo is as much about mahjong as Balatro is about poker, which is to say, not at all.

FTL: Faster Than Light

I’m not sure I’m fit to judge FTL: Faster Than Light just yet, but I’m liking it so far. It’s a not-really-real-time strategy roguelike where you manage a spaceship and fly around to fight other spaceships. It captures some of the feel of a tabletop RPG: combat is about positioning, smart weapon usage, and resource micromanagement; there are text-driven events where you get to make choices that impact your crew; and there’s dozens of numbers and stats to look at (and mostly ignore).

FTL is a challenging and punishing game, moreso than other roguelikes I’ve played. All the complexity is thrown at you from the start. There’s a combinatorial explosion of ships and systems and weapons and modifications and crew members. It suffers a bit from the oldschool roguelike fault of Guide Dang It! when it comes to things like knowing what each choice in an event does, or knowing that beams are effective against Zoltan shields, or even learning what each kind of sector has.

The game’s a classic, though, and I can see why. I’ve barely cracked the huge amount of content available in the game, and I can see myself sinking dozens of hours in the future. Let’s see how it goes.